Character Exercise

Become a Better Person Through this Brief Exercise in Character Development—Create Your Personal Portrait of the Good

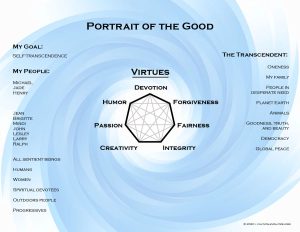

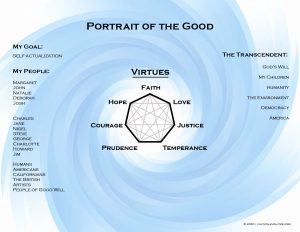

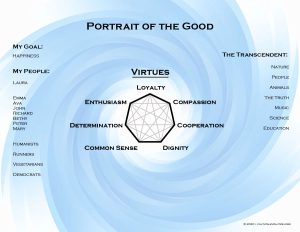

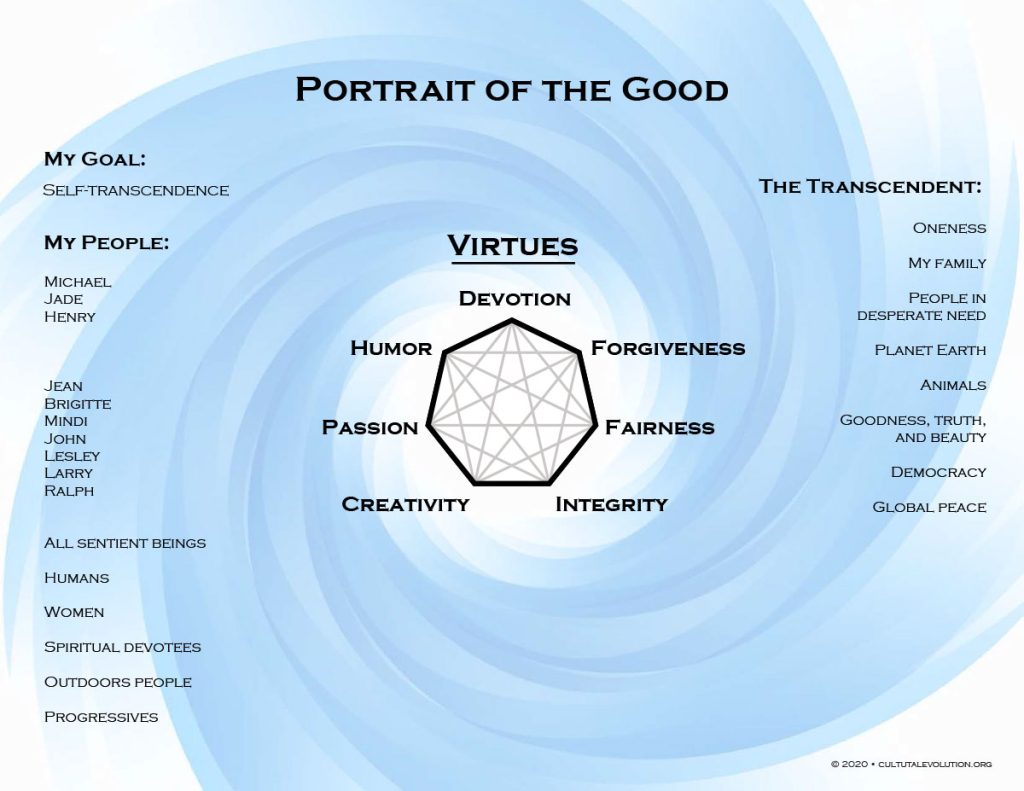

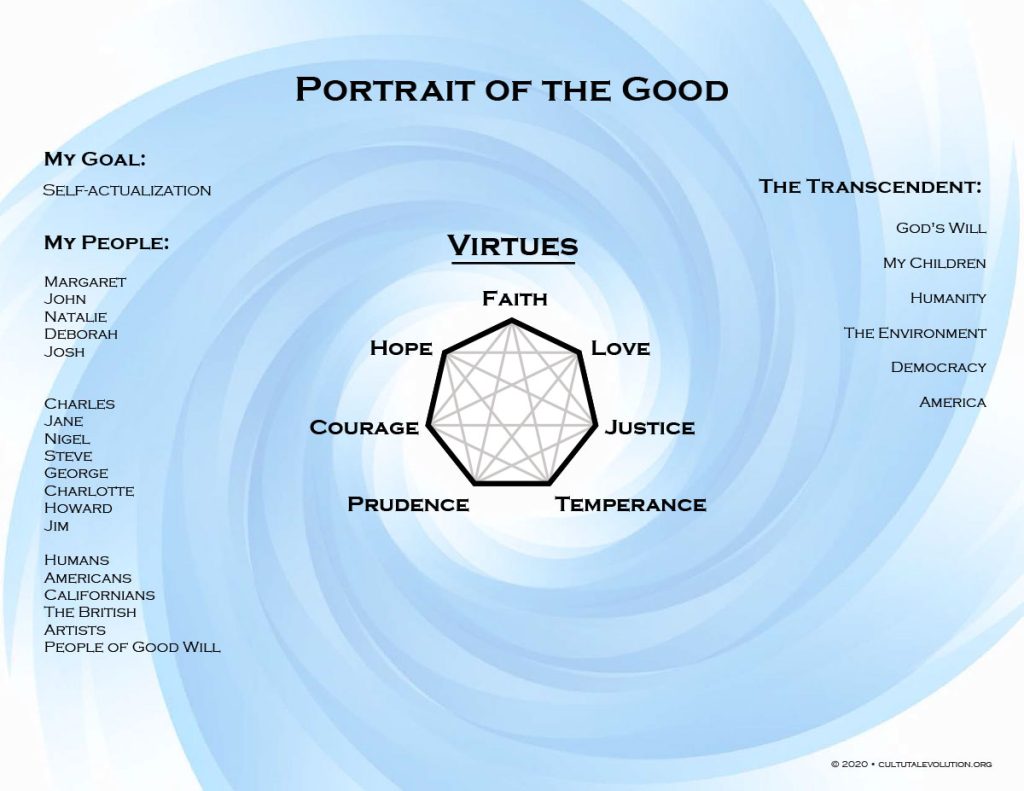

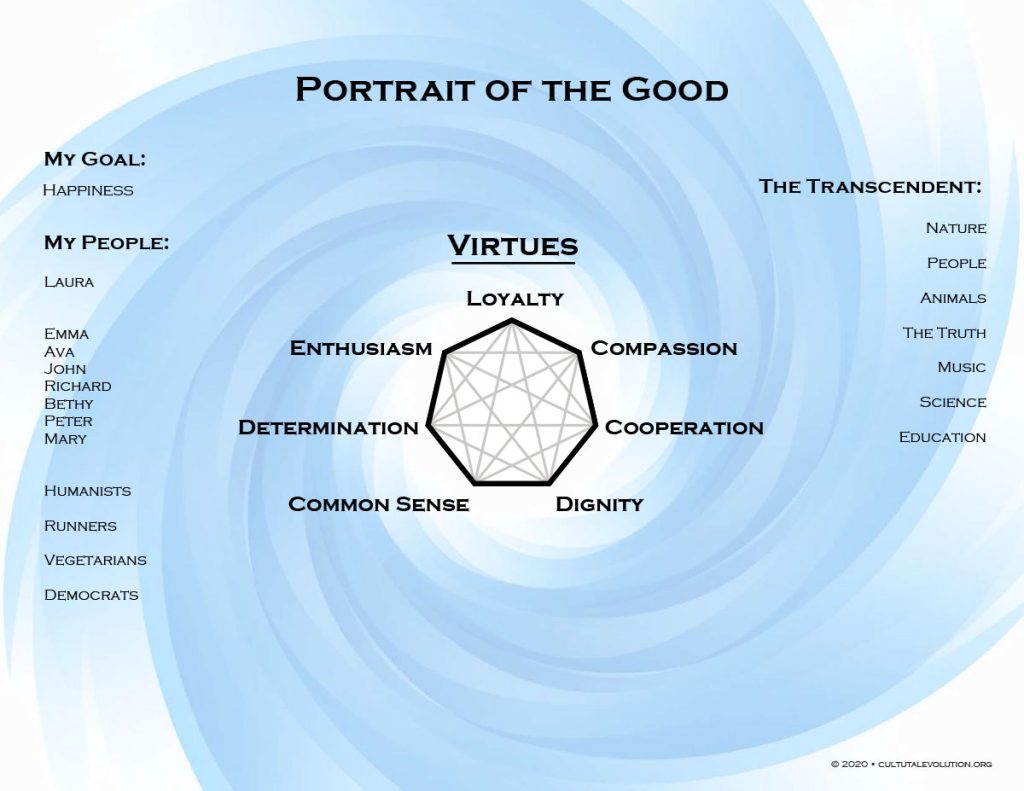

Answer 10 questions to create a personalized chart of what matters most to you. This chart—your Portrait of the Good—will be sent to your email address as a pdf file. Later, when you receive a broadcast email to our general list you may securely unsubscribe. That’s the deal. Examples of specific Portraits of the Good are shown below.

Three specific examples of completed Portraits of the Good (click to enlarge)

The point of this free exercise is to encourage the practice of virtues. This ancient practice develops your character and helps make you a better person. The exercise, which takes between 7 and 14 minutes, asks you to reflect on the people and things that matter most. This process helps clarify your highest ideals. Your answers create a printable personalized chart which serves as a practice tool for cultivating happiness and fulfillment. Your answers are confidential, your email will never be shared, and you can unsubscribe from our list at any time.

About the Portrait of the Good Character Development Exercise

This exercise is adapted from Steve McIntosh’s book: Developmental Politics—How America Can Grow Into a Better Version of Itself. It builds on time-tested teachings about the spiritual practice of virtues—teachings that are now experiencing a revival within secular positive psychology and academic moral philosophy. Virtues are character strengths, or commitments to personal excellence, whose practice results in personal growth. The practice of virtues involves cultivating the “habits of the heart” that help you do the right thing.

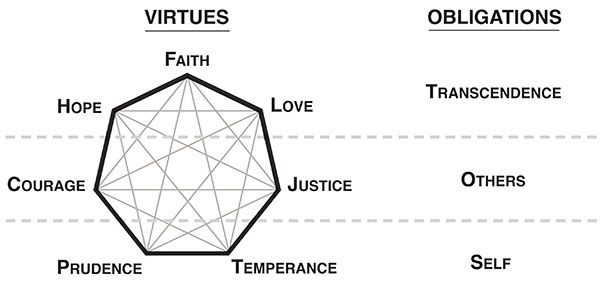

By asking you to identify the people and things you truly love, the exercise reveals the basic moral obligations you owe to yourself, to others, and to that which you recognize as transcendent (defined below). Contemplating these basic moral obligations, and working to live up to them, is how you practice virtues. The exercise accordingly asks you to select 7 specific virtues (from a list of 49 potential virtues) that best describe your highest ideals and expectations for yourself.

The connection between your chosen virtues and your moral obligations—to self, to others, and to the transcendent—is illustrated by this graphical figure. The specific virtues shown in this graphic are the 7 fundamental virtues (discussed below), but the specific 7 virtues you choose in this exercise may differ from these classical 7.

About the 7 Fundamental Virtues

The exercise asks you to select 7 personal virtues from a group of 49 virtue concepts. These 49 potential virtue choices are derived from the 7 fundamental virtues that have been recognized since antiquity. These 49 virtues, however, are not merely synonyms for the 7 fundamental virtues. The exercise’s 49 potential virtue choices represent the many different ways a person can be excellent. Knowledge of the 7 fundamental virtues is nevertheless useful for this exercise—and useful for life.

Although virtues were venerated by many classical civilizations, our contemporary understanding of virtues is rooted primarily in ancient Greek philosophy. For the Greeks, living a life of virtue was understood to be both a good in itself—the perfection of human nature—and the key to personal happiness. Plato summarized the list of “cardinal virtues” recognized by the society of his day as “temperance, prudence, courage (fortitude), and justice.” Plato was then followed by Aristotle who, in his famous treatise on virtues, laid the foundations for this field of moral philosophy by describing how each virtue is a mean between extremes, and how the various virtues form a unity in which each virtue is necessary for the full realization of the others.

The 4 cardinal virtues of the Greeks were then carried forward by Christianity, which combined these original four with Saint Paul’s 3 “theological virtues” of faith, hope, and love. This consolidated group of 7 virtues—justice, temperance, prudence, courage, hope, faith, and love—was subsequently validated and solidified philosophically by the seminal work of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Through the influence of Aquinas and others, these 7 fundamental virtues became part of the official Catechism of the Catholic Church and thus remain influential to this day.

But notwithstanding the Christian sanction of these classical 7, over the years hundreds of alternative ideals of virtue have been identified, and many different lists of preferred virtues have been proposed. There is, however, something very special or “fundamental” about these particular 7 virtues. Although many synonyms have been recommended as substitutes for these classical terms—for example, self-mastery for temperance, or practical wisdom for prudence—scholars working in the field of virtue ethics continue to be drawn to the specific ideas, if not the exact words, expressed by these ancient originals.

One of the strongest validations of the intrinsic significance of these 7 fundamental virtues has come from the field of positive psychology. In their influential 2004 book, Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification, prominent academic psychologists Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman summarized the findings of a significant body of empirical research which suggested a natural classification of 6 broad areas of virtue. Their research revealed “a surprising amount of similarity across cultures and strongly indicating a historical and cross-cultural convergence.” And the 6 basic kinds of character strength identified by Peterson and Seligman turned out to be remarkably similar to the 7 fundamental virtues. The only reason they came up with 6 rather than 7 “broad areas” is that they lumped hope and faith together into a single virtue they fittingly called “transcendence.” Positive psychology’s work on virtues continues to be pursued by the VIA Institute on Character.

What Does “Transcendence” Mean?

“Transcendence” or “the transcendent” generally refers to the people and things that are ultimately more important than yourself or your perceived self-interest. For example, that which is transcendent for you could include: Your family, humanity, your deepest convictions, the environment, God, Oneness, your country, animals, freedom, adventure, art, science, a better world, or anything you consider authentically “higher.” Your personal ideals of transcendence are grounded in the people and things that you’re dedicated to, and might even lay down your life for, if it became necessary. Your ideals of transcendence therefore help define your life’s higher purposes.

The word transcendence is used in this exercise as an umbrella term that is friendly to both spiritual and secular notions of transcendent higher purposes. In other words, you don’t have to be religious to recognize the significance of transcendent ideals. Our attraction to a greater good that lies beyond ourselves—our ceaseless striving to serve something higher and create something better—is a fundamental part of what makes us human.

How to Use Your Portrait of the Good to Practice Virtues

Once you have completed the exercise and received your personalized Portrait of the Good by email, take a moment to review and contemplate this chart of your highest virtues. Consider how practicing these virtues will make you a better person, and anticipate the sense of satisfaction that will accompany this personal growth. Keep your Portrait of the Good in mind as you go through life and work to make it a portrait of who you really are.

Here are ten simple practices that can help you use your Portrait of the Good to become a better person:

- Print out your finished Portrait of the Good on nice paper and put it in a prominent place in your personal space where you can review it frequently.

- Memorize your 7 chosen virtues. Repeat them out loud to yourself, tell your companions about them over a meal, and do your best to bring them to mind on a regular basis.

- Create a weekly ritual to chart the progress of your virtue practice. This was the technique Benjamin Franklin used to practice his famous list of thirteen virtues. Franklin focused on one virtue a week for thirteen weeks. At the end of each week he assessed his performance for that week’s virtue and recorded it in his journal.

- Write a short essay, blog post, or leave a comment below about what your chosen virtues mean to you, and what your practice commitment is. Explain, for example, which of your chosen virtues is the strongest and which needs the most work.

- Write a “Future Me” email (www.futureme.org) to yourself that will prompt you to check-in on how you’re doing with your virtue practice after some time has passed.

- Draw a symbolic picture of each of your 7 chosen virtues. Hand drawing a symbol for each of your virtues will help you keep them in mind. This process is proven to work as a mnemonic device.

- Combine your virtue practice with a mindfulness practice by repeating your specific list of 7 virtues to yourself just prior to bringing your awareness into the present moment.

- Start an affinity group or mutual improvement club, and meet once a month to discuss the practice of virtues and related topics.

- Create a “habit loop” by using a cue from something you see daily to remind you of your commitment to being virtuous. For example, when you look at yourself in the mirror, use that moment to remember the virtues that define who you want to be. Just as the mirror reflects your face, affirm your conviction that your character will reflect your virtues. And when you subsequently act in a virtuous way, reward yourself with a treat, or draw a small star on your Portrait of the Good. Celebrate your success!

- Read more about the power of virtues in one or more of these noteworthy books: The Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle, After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre, Natural Goodness by Philippa Foot, The Bourgeois Virtues by Deidre McCloskey, Ethics and Excellence by Robert Solomon, The Power of Character Strengths, by Niemiec and McGrath and Developmental Politics, by this exercise’s author, Steve McIntosh.